Heap Corruption Follow-up: Size, Alignment, and Crashing Collections

Alignment and buffers and tails, oh my!

Posted on by Greg Heo

After a massive multi-day effort, our team found one of those rare bugs that turned out to be an issue deep in the compiler. My colleague Agnes took the lead to track down the issue and wrote up her findings about her adventures.

Now that the issue is fixed and the hard work is done, I can step in and do a little post-mortem. 🔎 What was the problem? What was the fix? What did we learn?

Smashing the Stack

The classic article “Smashing the Stack for Fun and Profit” from 1996 outlines a technique to execute arbitrary (and possibly malicious) code via a program that doesn’t do proper bounds checking. In the 20 years since, operating systems and programmers have become much more clever about stopping these exploits.

Sometimes though we’re our own worst enemies — reading past the last element of an array or an off-by-one error that writes past the end of a buffer is as easy to do as it was 20 years ago.

In our case, we were getting heap corruption errors, meaning something was accessing memory it shouldn’t be accessing. But Swift is a safe language, isn’t it? How was this possible?

To get to the root cause, we first need to understand two concepts: memory layout, and tail allocation.

Memory Layout

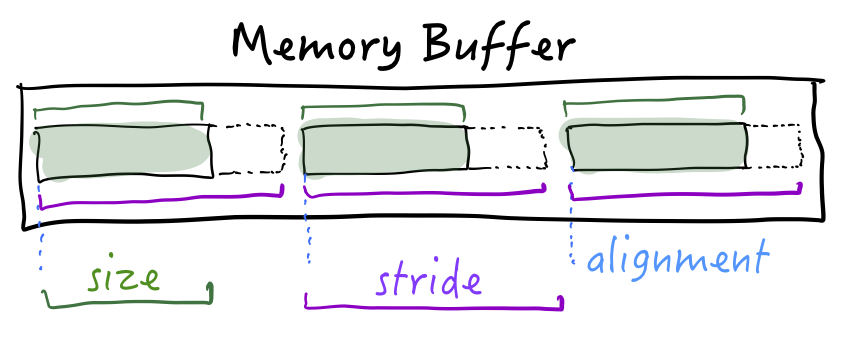

When instances are laid out in memory, there are several numbers to consider:

Size is the number of bytes to read so you have all the useful information.

Stride is the distance between two values. If you have a contiguous array of items, the stride is the number of bytes to advance to reach the next value.

Alignment helps determine where in memory your data can start. Depending on the type and the CPU, you could have requirements such as “data must start at an even memory address” or “data must start at a multiple of 8”.

If you want a longer discussion and more examples of memory layout, check out my article about Size, Stride, and Alignment in Swift.

Tail Allocation

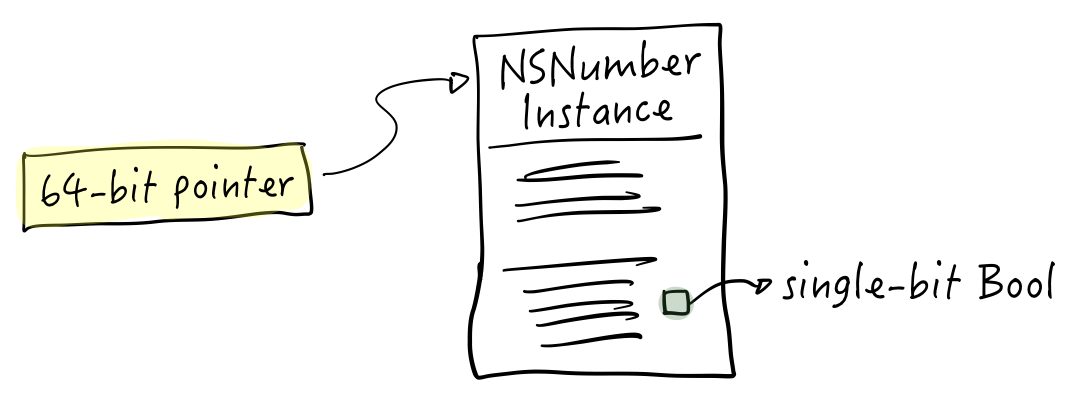

Do you remember tagged pointers from the Objective-C days? The idea was: why spin up an entire object just to hold something like an NSNumber containing a boolean? A boolean is a single bit, after all.

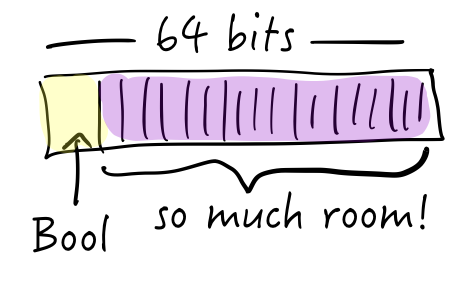

So on a 64-bit system, a pointer to an object takes 64-bits. But forget the pointer, we could store entire values with room to spare in 64 bits. Booleans, integers, even short strings could fit.

It’s a size optimization — although we could in theory address 264 bytes of memory (that’s 18 exabytes, or a 18 million terabytes), that’s overkill, isn’t it? Why not use a few bits for flags, leave enough space to address memory, and then you can support features like tagged pointers.

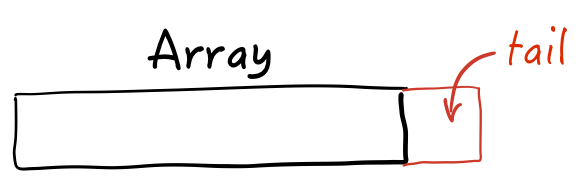

Similarly, when you allocate something like an array or dictionary in Swift you get a little extra space at the end.

Sometimes this is due to alignment: since the next thing in memory needs to spaced out a bit more, why not use that blank space “between” size and stride? Other times, the system might reserve a little extra space for expansion so you don’t need to do an expensive re-allocation and copy later. This extra space is the tail allocation.

Thanks to Karoly Lorentey for explaining tail allocation to me via Twitter.

Size, Alignment, and Crashing Collections

Now, on with the story.

Let’s say you want an array in Swift. The runtime goes ahead and allocates some space, and also adds on some tail-allocated space. Here’s the method that does the work:

|

|

We’re passing in an llvm::Value for the size, and the function returns another llvm::Value representing the new total size. For example, you ask for a 44-byte array and the function returns a value of 48 to round it up to a multiple of 8. That’s four extra bytes of tail-allocated storage!

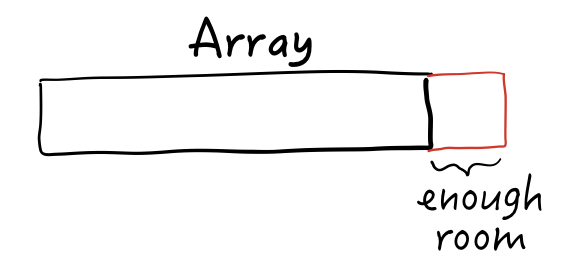

In practice, the system might add enough space for a few extra elements rather than just the “rounded up” space due to alignment.

Big Data

So, let’s say we have a array. We allocate enough space for some values:

Then the compiler helpfully adds on tail-allocated storage, enough to hold an additional value:

Now here’s the kicker: in our app, we’re storing values of double3 type. A double3 has a size and alignment of 32 bytes. But a 32-byte type will certainly fit in the tail-allocated space:

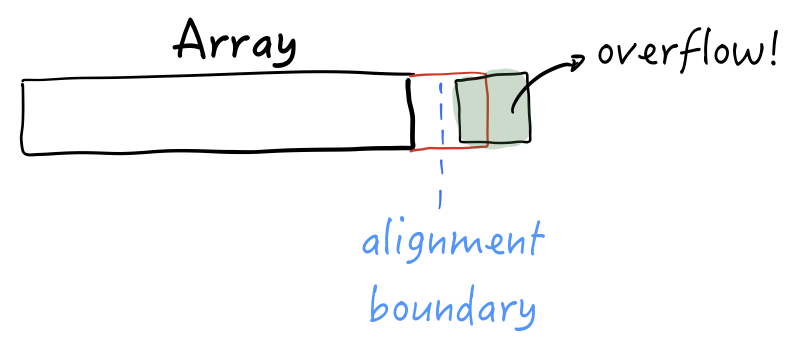

But it may not be aligned properly. At runtime, if the array decides to use its tail-allocated space it will also make sure to write that value to a 32-byte alignment boundary:

The tail-allocated size is sufficient, but the system didn’t take alignment into account. The alignment boundary we need is not at the start of the tail allocation.

The result? A buffer overflow. Corrupted heap. 💥

Alignment All the Way Down

What were the problems and solution here? Two things:

What gets stored in the tail-allocated space will affect the alignment of the entire type.

In the method declaration above, you saw how you pass in a size and get back a size. If you look at the commit that fixes the issue, the method now returns both a size and an alignment as a pair (aka a two-element tuple).

This change recognizes both size and alignment of the tail-allocated space when determining size and alignment of the overall space.

On Apple platforms, heap allocations are aligned on 16-byte boundaries.

That means your types that are 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 bytes wide are also aligned. But a

double3needs to be 32-byte aligned. This second commit updates the runtime to callAlignedAlloc()rather thanmalloc()to ensure proper alignment.

A big round of thanks to Erik Eckstein, Arnold Schwaighofer, Mike Ash, and Jordan Rose for their work and reviews on the two pull requests.

Final Lessons

I’m not a compiler engineer and I don’t know all the details about this bug, but I’m a firm believer in the value of reading code — especially code you don’t understand yet.

Agnes wrote a great summary of her lessons learned while tracking down this bug; what things can I add after digging a bit more into this problem?

Keep code distance short.

Tail allocation is a relatively new feature. It sort of bolts on top of the usual allocation flow, and there’s more code to follow and to understand to trace the thing end to end.

Sometimes this is a problem in my own code. Do classes have high levels of cohesion? Are related things close together, or separated by many frameworks and modules? How many files are there to go through and how big is the stack trace to understand some area of the code?

Learn how to trace values back in time.

Agnes covered the magic of going back in time (via TestFlight builds and version control) as a debugging tool.

Within your codebase, can you pick a variable and see its changes as it moves through your program? If the alignment is 1 at the beginning and 16 by the end, why? And how? Why isn’t it the correct value of 32? If the buffer looks correct before adding data and then has data written past the end after initialization, why? And how?

Learning how to use breakpoints, watchpoints, conditional breakpoints, etc. is invaluable here as you trace values over time.

Although it was tough work to track down this bug, I had a fun time doing a little digging after the fact on the cause and fix. I’m super impressed at how quickly it was fixed in the compiler and now look forward to the months ahead of a completely bug-free system. 😉

Thanks to my colleagues Agnes and Alexis for their help reviewing this article. All remaining errors are of course intentional and meant to test your attention. 😜

If you have questions or feedback for me, you can get in touch via Twitter where I’m @gregheo. If you’re interested in working with us — we’re hiring, and looking for an expert iOS developer. You could be working on the future of AR on iOS and writing about it on this fine company engineering blog!